“We can’t even anticipate what that’s going to do to society,” says Niedernhofer. “We do not have the bricks and mortar to house people if they’re not going to be taken care of at home, and we do not have the caregivers necessary. It’s scary, it’s really scary.”

Even more daunting, we’re not necessarily aging gracefully.

Individuals 65 and older have an exponentially increasing risk of chronic diseases like diabetes, heart disease, or dementia, she says. About 75 percent of people over 65 are going to have at least one chronic disease, and 25-30 percent will have two or more.

Says Niedernhofer: “Just being old is the number one risk factor for most chronic diseases.”

A bullseye on senescent cells

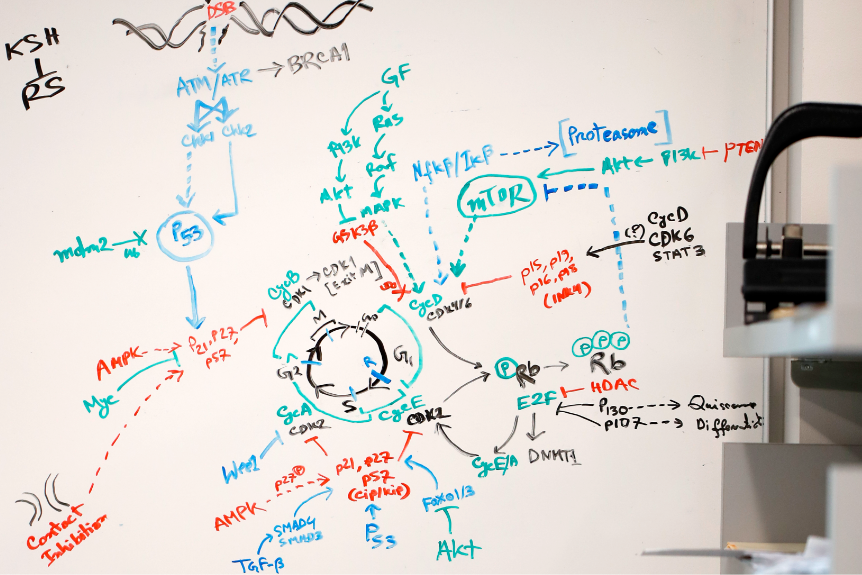

Niedernhofer’s work is in the emerging field of geroscience, which she defines as understanding fundamental aging biology and developing therapeutics that specifically target that. Her particular focus is trying to find a way to “prevent or delay all of the age-related diseases in a cluster.”

She was recruited to the University of Minnesota Twin Cities—along with her partner and colleague Paul Robbins—in July 2018 to co-direct iBAM, which is one of four Medical Discovery Teams (see sidebar) in the University of Minnesota System.

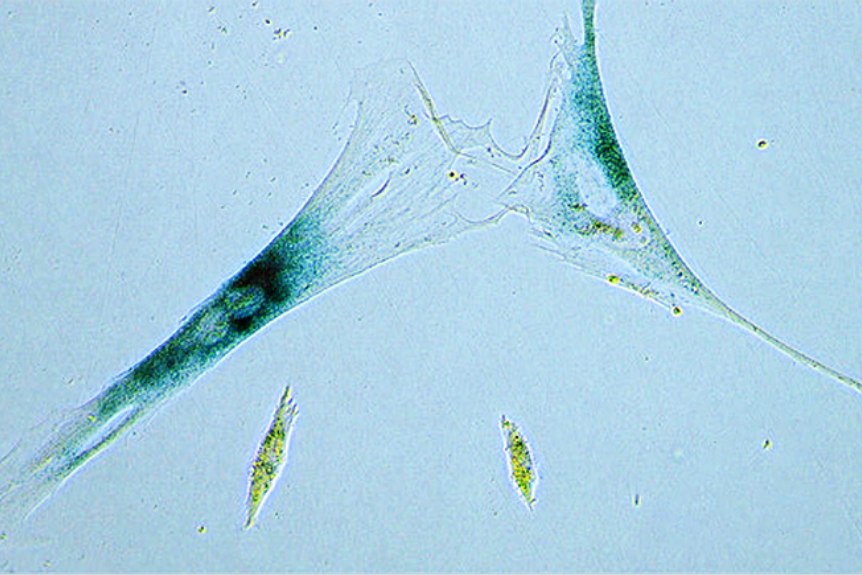

Niedernhofer is particularly focused on senescent (aging) cells. These are cells that no longer reproduce but that remain in the body. It’s estimated that for older adults, 3-10 percent of their cells are senescent. While they can have roles in tumor suppression and wound healing, senescent cells trigger the immune system and cause inflammation, which in turn makes people susceptible to age-related diseases.

Niedernhofer and Robbins—along with colleagues at Mayo Clinic—co-discovered a class of drugs they named senotherapeutics. They include senolytics (designed to clear senescent cells from the body) and senomorphics (which modify senescent cells).

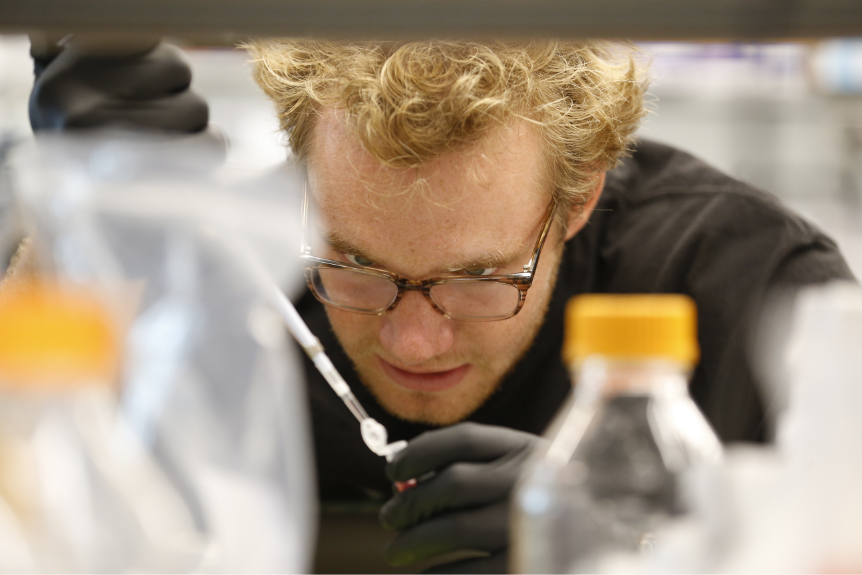

The scope of her geroscience research is impressive. Niedernhofer has a lab of about 30 people, while Robbins’ lab has about 20. They include everyone from undergraduates to senior staff scientists.

“There’s a lot of youth who are interested in this, which is really, really exciting,” beams Niedernhofer. “And the talent in the undergraduate pool here is just phenomenal. I love it. They’re so eager, and they’re really talented.”

Her lab is primarily focused on preclinical models of the human diseases of old age, which offer a tool for the testing required by the FDA. Robbins’ lab is more focused on drug development. Cumulatively, the iBAM team is involved with 40 active projects and 14 clinical studies on senolytic drugs.

“We make a brilliant team," says Niedernhofer. "We have been working on developing all sorts of senotherapeutics for different applications, and then working with leadership across the globe trying to figure out how to translate these—how to get them safely into clinical trials. And quickly.”

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, senolytics were also being tested as a treatment to fight COVID, and with promising results.

“The applications are almost limitless, at this point, and that’s why the U is so attractive, because we do everything here,” Niedernhofer says. “We’re experts in transplants and in infectious diseases and immunology.”

Brightening the golden years

Despite the dour statistics on aging and chronic disease, Niedernhofer is optimistic about her efforts in geroscience and in cracking the code on making aging a healthier proposition. She’s particularly intrigued by centenarians.

“They teach us that human biology is capable of healthy living beyond 100,” she says. “What’s really interesting about centenarians is, in the last few years of their life, they spend significantly less on health care than your average person—so [generally] they’re not sick, they’re not going to the doctor, they’re not taking pills. So, we can do this! We just have to figure out how they do it.”

“What we’re trying to do is extend the healthy period and not have this slow decline; that’s what we’re after,” she adds. “This is meant to extend healthy aging, not your lifespan.”

While she never envisioned herself wed to a career in geroscience, she fully realizes the gravity of her work.

“A career in science, to me, is a commitment to trying to help and to have an impact on health care, ultimately,” she says. “You pivot many times during your career to find the most important biomedical problem that you can study and where you can have the biggest impact. When I look around at our population, I think this is a big deal. And so, I am very passionate about it.”

The Institute on the Biology of Aging and Metabolism

The U of M’s Institute on the Biology of Aging and Metabolism (iBAM) is an interdisciplinary, trans-departmental effort across the University of Minnesota Medical School to advance research on the fundamental biology of aging. It’s one of four Medical Discovery Teams created through a generous investment in 2015 by the Minnesota Legislature.

The long-term vision of the Medical Discovery Team on the Biology of Aging and the Institute on the Biology of Aging and Metabolism is to discover ways to therapeutically target aging, which will allow older people in Minnesota and beyond to enjoy a longer “healthspan” (the period of good health in old age) and a better quality of life.

25

Clinical trials on senolytic drugs

73

iBAM Scientists

$6.7M

In NIA funding in 2023

33

Active projects

Share this story